In the remote parts of Central Sulawesi of the Indonesian archipelago, an-odd shaped island resembling a hunched-over letter “k”, under the Dutch known as Celebes, there can be found a saddle-roof style house type built on piles. Depicted on Dong Son drums as far back as 500BC-AD100, its origin suggests being of mainland Southeast Asia. The region is known as Tana Toraja, or Torajaland, and the characteristic house style is referred to as “tongkonan” – a traditional ancestral house of the Toraja people that inhabit these mist-shrouded valleys, averaging some 3000 feet above seas level. Visiting Sulawesi’s Toraja region is easily done from Bali and the experience is always a highlight of travel in Indonesia.

In the remote parts of Central Sulawesi of the Indonesian archipelago, an-odd shaped island resembling a hunched-over letter “k”, under the Dutch known as Celebes, there can be found a saddle-roof style house type built on piles. Depicted on Dong Son drums as far back as 500BC-AD100, its origin suggests being of mainland Southeast Asia. The region is known as Tana Toraja, or Torajaland, and the characteristic house style is referred to as “tongkonan” – a traditional ancestral house of the Toraja people that inhabit these mist-shrouded valleys, averaging some 3000 feet above seas level. Visiting Sulawesi’s Toraja region is easily done from Bali and the experience is always a highlight of travel in Indonesia.

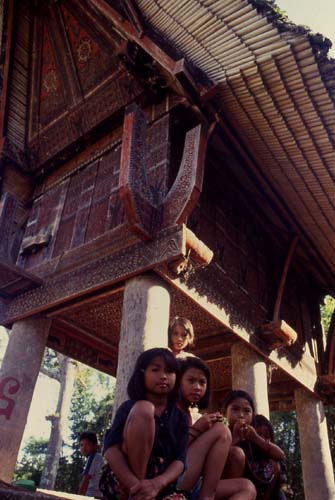

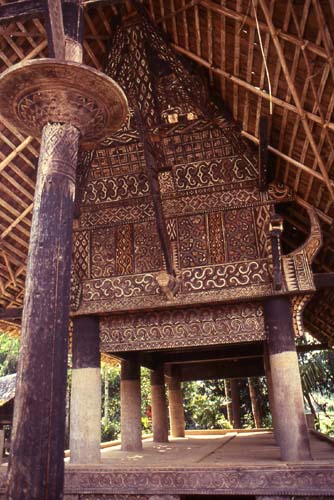

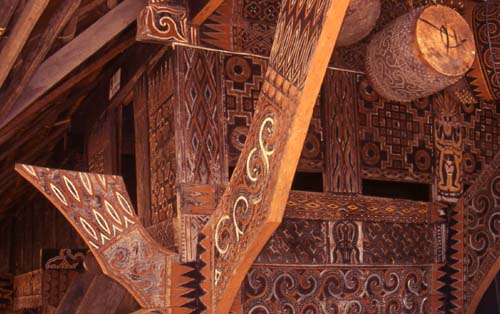

Of tongue-and-groove construction, using no nails, bolts or other metal fasteners, the traditional houses are built on solid tree trunk piles high above the ground to safeguard against rodents, snakes and dampness of the tropical ground. It is the massive roofs, covered in a layered bamboo, today often by corrugated iron, that immediately catch one’s attention. The research shows that these proto-Malay peoples have originated from Cambodia. Their own lore and legends claim that their ancestors crossed the high seas to the north, suggesting they embarked off the coast of Southeast Asia. Their stories tell of storm having diverted their boats to shores of Sulawesi, thrown ashore the people used them as roofs.

Of tongue-and-groove construction, using no nails, bolts or other metal fasteners, the traditional houses are built on solid tree trunk piles high above the ground to safeguard against rodents, snakes and dampness of the tropical ground. It is the massive roofs, covered in a layered bamboo, today often by corrugated iron, that immediately catch one’s attention. The research shows that these proto-Malay peoples have originated from Cambodia. Their own lore and legends claim that their ancestors crossed the high seas to the north, suggesting they embarked off the coast of Southeast Asia. Their stories tell of storm having diverted their boats to shores of Sulawesi, thrown ashore the people used them as roofs.

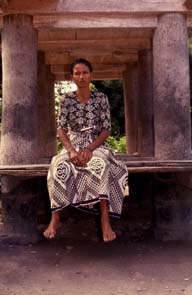

Fact is the characteristic house type Toraja build over centuries developed only in the interior mountains that surround fertile plateaus and valleys where they live. Due to the remoteness of the region, even today some seven hours by road to the main urban port of southern Sulawesi, the mountains have protected lifestyle and customs, which have changed relatively little to this day.

Fact is the characteristic house type Toraja build over centuries developed only in the interior mountains that surround fertile plateaus and valleys where they live. Due to the remoteness of the region, even today some seven hours by road to the main urban port of southern Sulawesi, the mountains have protected lifestyle and customs, which have changed relatively little to this day.

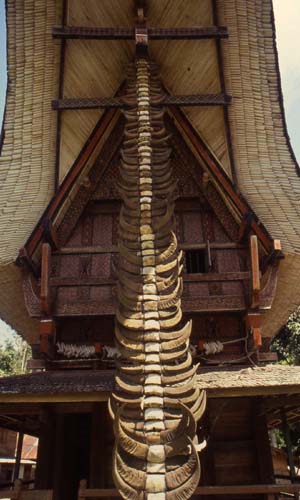

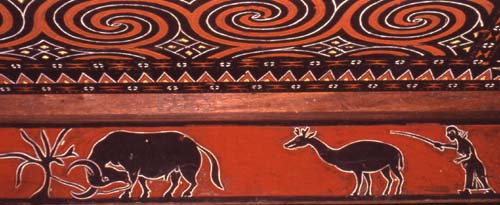

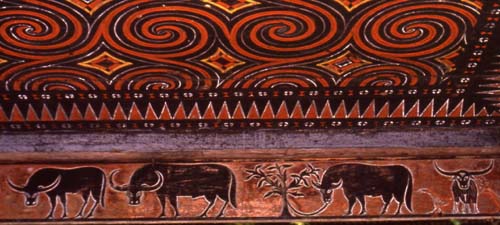

A legend has it that the roof shape as well as the general shape of the house is patterned on the ships on which they sailed from their ancestral homeland. On another hand, closer look at their culture reveals worship of buffalo, which is a symbol of fertility, strength, and a protection from evil, and its horns decorate the gables of Torajan houses, hence the other theory has it the roof shape is that of a buffalo’s horn.

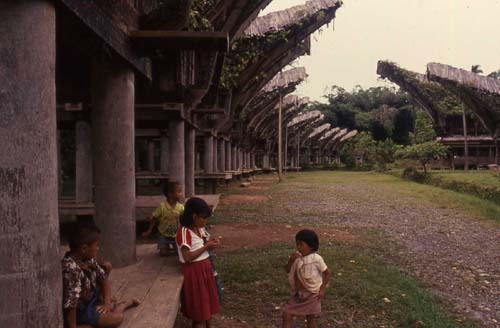

Whatever the shape’s origin the houses truly look as if they could sail, their sweeping roofs, especially when constructed closely together, the front of the house facing north, the direction of the ancestral homeland, look like ships moored at port. Opposite the houses are rows of granaries, too constructed in the same shape and on piles, often lavishly decorated. The uniform site plan of villages, compact settlements of freestanding structures set in a row, are precisely laid out as if based on well-thought out principles of a subdivision design.

The house type is always elevated off the ground but in some villages the front of yet longer and broader roof is supported by a massive pillar ever more so giving the house the appearance of a ship.

The house type is always elevated off the ground but in some villages the front of yet longer and broader roof is supported by a massive pillar ever more so giving the house the appearance of a ship.

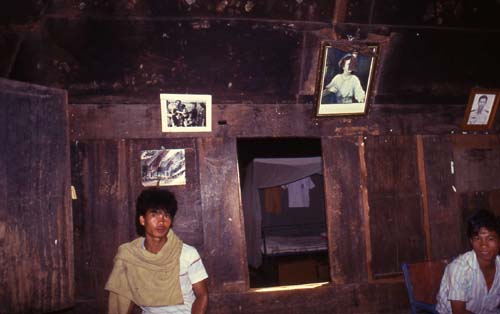

The interior of the house is quite simple, consisting usually of three rooms – a living area, kitchen and sleeping quarters. As there is no chimney soot of the large fire pit cooking area covers the beams and rafters.

cialis women

Every house, typically on the front facade but often also on the side of the house, adorn horns of buffalos. The family status is usually shown by the number of horns mounting the house, the more there are the higher the merit and status for the family, attesting to many sacrifices, feasts and ceremonies performed by the family to which many guests have been invited.

Every house, typically on the front facade but often also on the side of the house, adorn horns of buffalos. The family status is usually shown by the number of horns mounting the house, the more there are the higher the merit and status for the family, attesting to many sacrifices, feasts and ceremonies performed by the family to which many guests have been invited.

In the ancient times, the old, “adat” ceremonies and animistic rites, practiced by the Toraja until the arrival of Christian missionaries, not only buffaloes were sacrificed but people as well. As in many other cultures of the Indonesian archipelago, from Sumatra to Timor, headhunting was part of animistic practices. Its existence shows relationship to headhunting practices of ancient cultures of South and Southeast Asia, further substan

ut prescription’>cialis online without prescription

tiating the roots of origin of the island cultures, whether of Indonesian or Philippine archipelago. Although buffalo and pig sacrifices have replaced human heads and the animistic religion has for the most part been diluted, reasonably strong adat practice still continues to this day and is practiced by about 25% of the Toraja people. Much of the traditional animistic practices take place during the funeral ceremonies called the Feast of the Dead. The practice is sustained by the Toraja inherent belief in afterlife, called Puya, or the Land of the Dead, where everyone is believed will live under the same conditions as he or she did on earth, a belief that spurs every Torajan to attain as much wealth as possible during his lifetime. Another belief of note is that the Toraja people believe the souls of animals will follow their masters into heaven, thus the buffalo sacrifice is in a way not perceived as taking of life as such but rather as an act which is only a temporary state of parting between man and beast and the two will reunite once again at death.

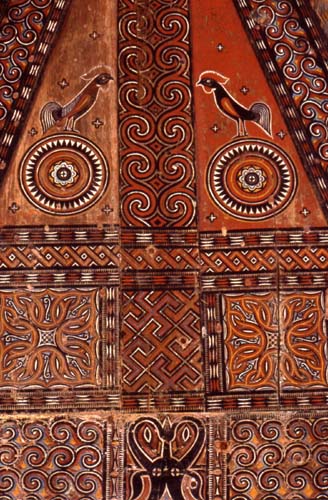

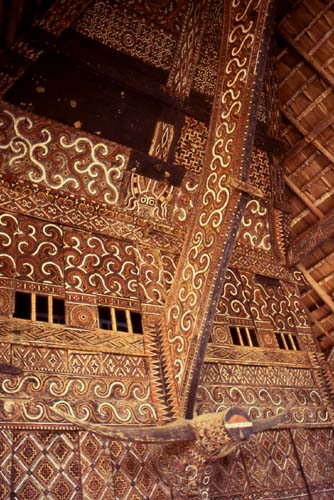

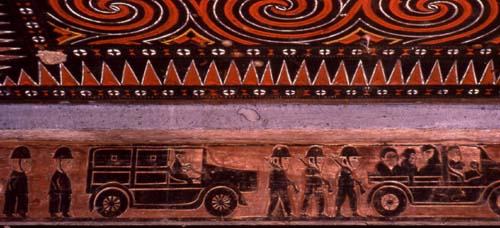

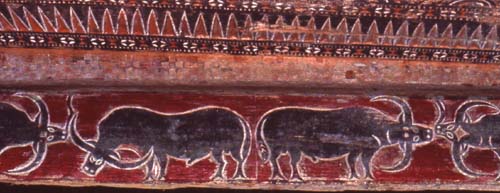

All Toraja houses are richly decorated in a maze of geometric ornamentation in ochre-red, black and white as well as a profusion of symbolic carvings representing aspects of ancestral worship, known as Aluk Todolo. Traditionally people were only allowed to depict motives characteristic of their social status or cast, whether that of the Tokapua or the noblemen, the Tomokaka or a middle-class tradesmen, or the Tobuda, the commoner, usually a farmer. Today people add designs expressive of their lifestyle as well as profession.

All Toraja houses are richly decorated in a maze of geometric ornamentation in ochre-red, black and white as well as a profusion of symbolic carvings representing aspects of ancestral worship, known as Aluk Todolo. Traditionally people were only allowed to depict motives characteristic of their social status or cast, whether that of the Tokapua or the noblemen, the Tomokaka or a middle-class tradesmen, or the Tobuda, the commoner, usually a farmer. Today people add designs expressive of their lifestyle as well as profession.

Most Toraja people are Christians, both Catholics and Protestants, and the church spires dot the horizon of the villages. Only about ten percent are Muslim, and in fact Muslim religion dominates the coastal areas as well as many deep valleys surrounding the Toraja region as such. All in all Toraja continue to practice highly ritualistic religious ceremonies including the rites of fertility, marriage, birth and death.

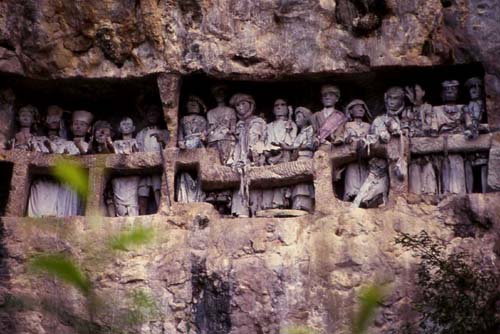

The Torajans believe that when a person dies, the soul leaves the body but remains restless until the burial ritual has been completed. Often a time much of family’s wealth can be spent on staging the finest, most elaborate funeral they can afford, a strange blending of solemnity and celebration. Today the Toraja may bury their dead in the ground but the traditional burial was by placing the body in a casket that was taken into a small structure shaped like their house before being moved to its final resting place inside a cliff-side grave. The caskets were inserted inside cave-like chambers although often left to protrude on specially constructed balconies high above the valley floor. As over time many caskets fell, the ground below is littered with bones and skulls. On the balconies are displayed “tau-tau”, the wooden effigies of the deceased, typically set in rows as puppets they stand gazing over the countryside.

The Torajans believe that when a person dies, the soul leaves the body but remains restless until the burial ritual has been completed. Often a time much of family’s wealth can be spent on staging the finest, most elaborate funeral they can afford, a strange blending of solemnity and celebration. Today the Toraja may bury their dead in the ground but the traditional burial was by placing the body in a casket that was taken into a small structure shaped like their house before being moved to its final resting place inside a cliff-side grave. The caskets were inserted inside cave-like chambers although often left to protrude on specially constructed balconies high above the valley floor. As over time many caskets fell, the ground below is littered with bones and skulls. On the balconies are displayed “tau-tau”, the wooden effigies of the deceased, typically set in rows as puppets they stand gazing over the countryside.

There is definitely more to Indonesia than Bali and visiting Sulawesi and Torajaland should not be missed. On your next trip to Bali or elsewhere in Indonesia include Sulawesi in your itinerary!